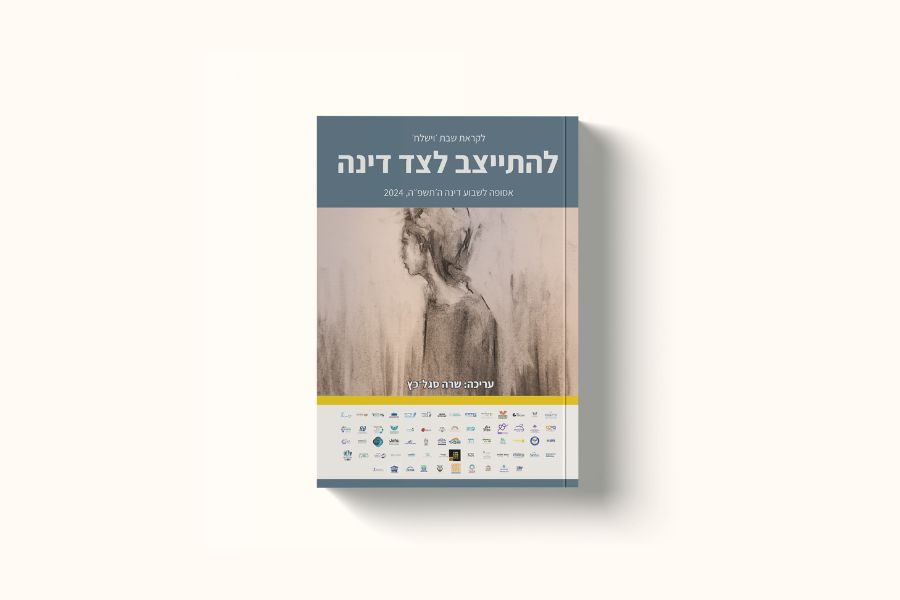

פורסם בנובמבר 2023 במסגרת ׳שבת התייצבות לצד דינה׳:

רשומה זו נכתבת לקראת קריאת פרשת ״וישלח״, אשר מכילה את סיפור דינה בת יעקב ולאה, כחלק מסדר פרשות השבוע הפרושות על פני השנה. הרקע לכתיבת הרשומה הוא כמובן מיקומנו על לוח השנה, אך בו זמנית היא נכתבת מתוך ההקשר החברתי של העיון בסיפור דינה, ועל בסיס הכרה כאובה במעשי הפגיעה והאלימות הנוראיים שנכפו על החברה הישראלית והיהודית בבוקר שמחת תורה. נקודת המוצא לבחירה לעסוק בצורה יזומה בסיפורה של דינה ולהצביע, עם כל הקושי והכאב, על הרלוונטיות החזקה מתמיד של סיפור זה בחיינו – היא עמדה המצהירה כי תם עידן ההחרשה וההצנעה סביב פגיעה מינית ואלימות מכל סוג שהן.

The English version follows the Hebrew version

אזהרת טריגר

Trigger Warning

התוכן שלפניך עשוי להיות קשה לקריאה ומעורר רגשות של עצב וכאב.

אפשר לבחור לדלג ואפשר לבחור לעצור באמצע הקריאה.

מומלץ להקשיב לעצמך בזמן הזה.

סיפורה של דינה, על סדר הופעתו בטקסט המקראי, הוא סוג של נייר לקמוס בכל מה שקשור לבחינת נורמות הקהילה והמשפחה בתקופת המקרא הקדומה, יחסי כוח והסוגיות הכואבות של אונס, אלימות ופגיעה מינית. ואכן, לטקסט זה פירושים רבים והעיון בו מרובה פנים ועמדות. בבואנו לעסוק בסיפורה של דינה ובטקסט המקראי, ראוי להבחין בין שתי מסגרות פרשניות עיקריות: הפרשנות המסורתית-קלאסית והפרשנות המודרנית-ביקורתית. בעוד הראשונה משתמשת לרוב בטכניקה צמודת טקסט ונוטה להתמקד בשאלות ותמות מסוימות מתוך פרספקטיבה מסורתית-היררכית וגברית, האחרונה מרחיבה את גבולות המעשה הפרשני וכלי הפרשנות, מאפשרת ומייצרת נקודות מבט נוספות ומשמיעה לעיתים קול שלא היה יכול להישמע בעבר.

"ותצא… ויקח" – פרשנות מסורתית

כידוע, סיפורה של דינה מופיע בפרשת "וישלח" בספר בראשית, פרק ל"ד:

"וַתֵּצֵא דִינָה בַּת לֵאָה אֲשֶׁר יָלְדָה לְיַעֲקֹב לִרְאוֹת בִּבְנוֹת הָאָרֶץ׃ וַיַּרְא אֹתָהּ שְׁכֶם בֶּן חֲמוֹר הַחִוִּי נְשִׂיא הָאָרֶץ וַיִּקַּח אֹתָהּ וַיִּשְׁכַּב אֹתָהּ וַיְעַנֶּהָ׃ וַתִּדְבַּק נַפְשׁוֹ בְּדִינָה בַּת יַעֲקֹב וַיֶּאֱהַב אֶת הַנַּעֲרָ וַיְדַבֵּר עַל לֵב הַנַּעֲרָ׃ וַיֹּאמֶר שְׁכֶם אֶל חֲמוֹר אָבִיו לֵאמֹר קַח לִי אֶת הַיַּלְדָּה הַזֹּאת לְאִשָּׁה׃ וְיַעֲקֹב שָׁמַע כִּי טִמֵּא אֶת דִּינָה בִתּוֹ וּבָנָיו הָיוּ אֶת מִקְנֵהוּ בַּשָּׂדֶה וְהֶחֱרִשׁ יַעֲקֹב עַד בֹּאָם׃" (בראשית ל"ד, א-ד)

פסוקים אלו מתארים את נקודת ההתחלה של עלילה רבת משתתפים: דינה, שכם, חמור אבי שכם ונשיא העיר שלם, תושבי העיר שלם, יעקב, בני יעקב-אחי דינה בכלל ושמעון ולוי בפרט. העלילה מוכרת – לאחר 'לקיחת' דינה על ידי שכם ורצונו לשאת אותה לאישה, חמור אבי שכם ומנהיג הקהילה פונה ליעקב ומשפחתו בבקשה להסדיר נישואים אלו מתוך מוכנות לשאת ולתת מה שידרש לשם כך. בני יעקב דורשים מחמור וקהילתו למול כל זכר במטרה להפוך ל"עם אחד" (בראשית ל"ד, טז) ולאחר שכנוע של חמור ושכם את בני עירם, מתבצעת מילה המונית של כל הזכרים בעיר. בעת מכאובם, הורגים שמעון ולוי כל זכר, לוקחים את רכושם וצאנם, שובים את הנשים והילדים ולוקחים את דינה מן העיר. יעקב מעמת את בניו עם מעשיהם, אך האחים מתעקשים על צדקתם:

"וַיֹּאמֶר יַעֲקֹב אֶל שִׁמְעוֹן וְאֶל לֵוִי עֲכַרְתֶּם אֹתִי לְהַבְאִישֵׁנִי בְּיֹשֵׁב הָאָרֶץ בַּכְּנַעֲנִי וּבַפְּרִזִּי וַאֲנִי מְתֵי מִסְפָּר וְנֶאֶסְפוּ עָלַי וְהִכּוּנִי וְנִשְׁמַדְתִּי אֲנִי וּבֵיתִי: וַיֹּאמְרוּ הַכְזוֹנָה יַעֲשֶׂה אֶת אֲחוֹתֵנוּ׃" (בראשית ל"ד, ל-לא)

העלילה הדרמטית, שגם בקריאה 'פשוטה' מעוררת הרבה מחשבה ושאלות, זוכה כמובן לפרשנות רבה מצד פרשני הטקסט המקראי, כאשר ניתן לזהות מוקדי עניין ועיסוק משותפים בקרב הפרשנים:

- דמותה של דינה עצמה וחלקה בהשתלשלות העלילה: האם יש בה 'אשם' ושהתנהגותה היא זו שהביאה לידי מצב זה או האם לא עשתה כל רע?

- משמעותה של פעולה הלקיחה של שכם את דינה והמניע לפעולה זו: האם מדובר באונס או לא? האם המניע קשור בסטטוס וכבוד הנובעים מעמדתו של יעקב והיותה דינה בתו יחידתו, באהבה או אולי בחשק מיני בלבד?

- מעשה הנבלה ומוקד הצער והנקמה: האם מעשה הנבלה הוא מעשה האונס, קיום יחסי מין של ערל עם בת ישראל בכלל ובת יעקב בפרט, או שמא מדובר בכלל באי בקשת הרשות מראש מאבי המשפחה בהתאם לנורמות בעת הזו? הפגיעה אינה בהכרח בדינה אלא בכבוד המשפחה ובנוהג המקובל.

- מיהם.ן האשמים.ות ומי נענש על מה?

ישנם קווי דמיון השזורים בין המקורות הפרשניים המסורתיים: התמקדות ביעקב ומעמד המשפחה וכן בשאלת מעשה הנבלה שנעשה והשפעותיו, לצד 'חקירה' של התנהגות דינה. דינה עצמה, רצונה וההשלכות על חייה, לא זוכים לתשומת לב רבה מצד הפרשנות המסורתית. דינה מופיעה כמובן פה ושם, אך בדומה לנוכחותה הדלה בפשט, היא גם איננה 'שחקנית' מרכזית בסיפור הפרשני. העיון בדמותה מתמקד לרוב בפסוק הפותח של פרק ל"ד: "וַתֵּצֵא דִינָה בַּת לֵאָה אֲשֶׁר יָלְדָה לְיַעֲקֹב לִרְאוֹת בִּבְנוֹת הָאָרֶץ" (בראשית ל"ד, א). הפרשנים מנתחים את משמעות יציאתה של דינה וראייתה בבנות הארץ. רבים מהפרשנים מתארים את יציאתה כפעולה לא צנועה (יציאה=יצאנית) ואף דורשים כי כוונתה הייתה להשוויץ בפני בנות הארץ [1]. כלומר, מדובר בעמדה שתולה מידה מסוימת, לא מבוטלת, של אשמה בנעשה בדינה עצמה ובהתנהגותה. עמדה אחרת מדגישה דווקא את 'חפותה' של דינה, בין אם על בסיס ייחוסה ליעקב וללאה כעדות להתנהגותה הנאותה וצניעותה, ובין אם מתוך ניתוח מעשי שכם וזיהוי מעשיו כגורמים העיקריים להשתלשלות האירועים [2]. כאמור, בהמשך הפרשנות אינה מתמקדת בדינה אלא בשאלות שתוארו: במוטיבציה של שכם, במשמעות של מעשה הנבלה וכן הלאה.

כשבוחנים דיון זה במבט עכשווי, לא ניתן שלא להתייחס לכך שמדובר במובנים רבים בגרסה קדומה של הנטייה ל"האשמת הקורבן" ובמחיקה של האישה ממערכת השיקולים וההכרעות. ברור שמדובר באנכרוניזם ובביקורת מודרנית לחלוטין, אך בראייה חברתית ומוסרית זהו אנכרוניזם הכרחי לשם הכרה בבעייתיות של דיונים ופרשנות מסוג זה.

רוצה לקבל עדכונים ממגזין גלויה?

הפרטים שלך ישארו כמוסים וישמשו רק למשלוח אגרת עדכון מהמגזין מפעם לפעם

"וזוהי צעקה שבלב" – פרשנות מודרנית

העיון המודרני מתבסס על כלים רבים של ביקורת טקסטואלית-ספרותית לצד ניתוח היסטורי ומחקרי, ומאפשר ריבוי של נקודות מבט מעבר למסורת הקלאסית. מציאות פרשנית זו אפשרית רבות בזכות התנועה הפמיניסטית ונוכחות נשים במרחב הפרשנות והשיח במקביל למגמת העיצוב או הגילוי המחודשים של ההיסטוריה (בזווית הנשית-נקבית למשל, יש את מגמת ה"היא-סטוריה"). פרשנות מודרנית ופמיניסטית, יכולה לחלץ מן הטקסט המקראי קולות שלא נשמעו בפרשנות המסורתית, להצביע על מבנים חברתיים ופוליטיים ולפרק יחסי כוח ושליטה [3]. היא מסוגלת לבחון את העבר, ההווה והעתיד בעיניים של צדק חברתי, מוסר ואתיקה בת זמננו.

לאור התוכן הדרמטי של פרק ל"ד בספר בראשית, לא פלא הוא שאין ספור מאמרים, דרשות וטקסטים ספרותיים נכתבו בעשורים האחרונים על סיפורה של דינה ומעשי שכם, שמעון ולוי ויעקב. בשונה מהנטייה של הפרשנות המסורתית, ישנה מגמה ברורה הקיימת בפרשנות המודרנית להציב דווקא את דינה במרכז ולתת דין וחשבון על שנעשה לה. דוגמה בולטת לכך היא למשל ספרה של אניטה דיאמנט, 'האוהל האדום', שהינו רומן העוסק כולו בדמותה של דינה ונקודת מבטה [4]. דיאמנט בוחרת להציג מחזה טרגי של אהבה ורצון הדדי בין דינה ושכם, שנקטעים באלימות רצחנית ובטבח שכם ועירו על ידי אחיה של דינה. ספרה של דיאמנט נתפס בעיני רבים כאקט פרשני מחאתי ופמיניסטי שמעניק זהות וקול לדינה, לרצונותיה, למאוויה ושמציב אותה כסובייקט. אולם, יש שרואים בספר זה מהלך אנטי-פמיניסטי לאור 'צידוד' העלילה בשכם ומעשיו ומסגור ההתרחשות כסיפור אהבה טרגי ורומנטי תוך התעלמות מההיבטים האלימים של מעשה שכם על פי הטקסט המקראי. במונולוג 'אני דודתה של שרה, ורחל הייתה דודתי' [5], מציגה מירה מגן, באופן זהה לדיאמנט, את נקודת מבטה של דינה. אולם, המונולוג מציע פרשנות הפוכה לגמרי למעשי שכם ולרגשות דינה מהפרשנות של 'האוהל האדום':

"…כשבא שכם ועשה בי מה שעשה, לא היה לי צמר עיזים לנשוך, ויצאה ממני הצעקה שחנקתי והייתה גדולה וחזקה. 'אל תצעקי ילדה' אמר שכם, 'אני אוהב אותך, אני אתחתן אתך, ירבו עלי מוהר כמה שירבו, ילדה, אני אתחתן אתך.' כל כך אני מתפללת שתחזור אלי הצעקה היחידה שצעקתי, ואצעק אותה שוב."

הטקסט מציג בבירור כי מבחינת דינה, מדובר במעשה לא רצוי, ביחסי מין שנכפו עליה באלימות ובאי הסכמה – באונס.

רבקה לוביץ מדגישה את הממד של הכפייה והאינוס שעוברת דינה ואת שתיקתה הרועמת. היא דורשת ומפרשת את סיפורה של דינה במתודיקה דומה למדרש פרשני קלאסי, אך מתוך נקודת מבט נשית-נקבית [6]:

"'ותצא דינה.. לראות בבנות הארץ' – דינה זנב לאחֶיה הייתה, משגדלה ראתה שאין מקומה אתם, יצאה לראות בבנות הארץ, הוא שנאמר או חברותא או מיתותא. דינה כאילמת הייתה, הוא שנאמר 'ותצא דינה … לראות': לראות יצאה, ולא לשמוע. ועוד שנאמר 'וישכב אותה ויענהָ' ולא נאמר 'ותצעק דינה'. וכי יעלה על דעתך שלא צעקה דינה? אלא כאילמת נהייתה, שמחמת הכאב ומחמת הבושה נשתתקה ונדמה.

שלא לרצונה היה הדבר. הכתוב אומר 'ויקח אותה', מלמד שחטף אותה שכם. ועוד אומר הכתוב 'וישכב אותה' – 'אותה' נאמר ולא 'עמה', מלמד שכפה עצמו עליה. ועוד אומר הכתוב 'ויענהָ', כפשוטו.

שתיקתה של דינה מסוף העולם ועד סופו, וזוהי צעקה שבלב…"

דיאמנט, מגן ולוביץ הן רק אחדות מרבות.ים וטובות.ים שעסקו בסיפורה של דינה ונעשה בפרשה. הן מדגימות את הרחבת הגבולות הפרשניים, את הקולות הנוספים שהועלו אל פני השטח ואת היכולת והצורך לעסוק בסוגיות כואבות וקשות.

להטות שכם אל דינה

הדרשנות והפרשנות המודרנית בסיפור דינה אינן מובנות מאליהן. לא מדובר בנושא שעמד במוקד שיח קהילתי או רוחני לפני אי אלו עשורים, אלא בכזה שאפילו עורר מבוכה בקריאה בבית הכנסת ושממנו היה עדיף להתחמק שמא יעורר דיון בשאלות לא נעימות. המבט המודרני מאפשר לנו לבחון ללא מורא את הדמויות בסיפור: שכם וחמור, יעקב ובניו, ולעמת את מעשי הדמויות נוכח דינה כסובייקט עצמאי ובעל קול. בעת הזו, על כל מכאוביה, אנחנו מבקשות ומבקשים להטות שכם אל דינה ולעמוד לצדה. מוטלית עלינו החובה לקריאה פרשנית שמכירה בקולו של הפרט הפגוע ו/או המושתק, ובאחריותן של הקהילה והחברה לקידום אמות מידה של צדק, חמלה ושאיפה לתיקון.

לעיון ודיון בפרשה ובסיפור דינה – מוזמנים ומוזמנות לפנות אל הרשומה האינפורמטיבית שהעלינו במגזין גלויה, אשר מאגדת טקסטים ומקורות רבים ולשימוש מגוון.

תכנים נוספים על ״שבוע דינה״:

הערות שוליים והפניות:

[1] רש"י, רד"ק, אור החיים, מדרש אגדה (בובר), בראשית רבה, מדרש לקח טוב שם, מדרש שכל טוב שם, פירוש הדר זקנים ועוד רבים אחרים על בראשית ל"ד פסוק א'. התמקדות ב"ותצא", בייחוסה של דינה ללאה (שגם יצאה) ומיקום יציאתה של דינה על ציר של יצאנות המתאימה לנוהגות בזנות ובחוסר צניעות.

[2] רשב"ם, המלבי"ם, הרש"ר הירש, פרקי דרבי אליעזר, ביאור ישר ועוד.

[3] פרשנות פמיניסטית, דבורה עברון (הדברים נאמרו ביום העיון לזכר אהובה בן-אהרון).

[4] אניטה דיאמנט, האוהל האדום (תרגום: שרונה גורי), הוצאת מטר, תל-אביב 2000.

[5] 'אני דודתה של שרה, ורחל הייתה דודתי', בתוך רותי רביצקי (עורכת), קוראות מבראשית, תל אביב, ידיעות אחרונות וספרי חמד. 1999, עמ' 275–279.

[6] רבקה לוביץ, 'סיפור דינה: המקרא, חז"ל ואנחנו', אבי שגיא ונחם אילן (עורכים), תרבות יהודית בעין הסערה: ספר היובל ליוסף אחיטוב, הקיבוץ המאוחד תשס"ב, עמ' 742–753.

קווי החירום לנפגעות ולנפגעי תקיפה מינית

שאלון זיהוי למצבי סיכון

שאלון אנונימי של משרד הרווחה שנכתב עם מומחים לטיפול

כדי לזהות את מצבך או את מצב הסיכון של בן או בת משפחה ובסביבתך הקרובה.

רוצה לקבל עדכונים ממגזין גלויה?

הפרטים שלך ישארו כמוסים וישמשו רק למשלוח אגרת עדכון מהמגזין מפעם לפעם

Shoulder to Shoulder Alongside Dinah | The team of Gluya Magazine

This article was written in the days leading up to Parshat Vayishlach, the weekly Torah reading that includes the story of Dinah, the daughter of Yaakov and Leah. The chronological background is, naturally, the relevant time of the year, but it is also written in the social context of reading Dinah's story, and the painful recognition of the terrible assault and violence wreaked on Israeli and Jewish society on the morning of Simchat Torah. The starting point for choosing to address Dinah's story and, with all the associated difficulty and pain, its stronger than ever relevance to our own lives, is a stance that proclaims the end of the era in which mention of sexual assault and any kind of violence is silenced and suppressed.

Trigger Warning

The content here may be difficult to read and may evoke feelings of sadness and pain.

You can choose to skip it or to stop reading in the middle.

Try to listen to yourself at this time.

Dinah's story, as it appears in the biblical text, is a kind of litmus test for examining communal and family norms during the early biblical era, power relations and the painful issues of rape, and sexual assault and violence. Indeed, this text has numerous interpretations and reading it reveals multifaceted commentaries. When coming to address Dinah's story and the biblical text, it is appropriate to distinguish between two fundamental interpretive frameworks: the classic-traditional interpretation and the critical-modern interpretation. Whereas the first generally employs an approach that adheres to the text and tends to focus on certain questions and themes out of a moral-hierarchical and male perspective, the latter expands the boundaries of the interpretive act and of its tools, enables and creates further viewpoints and, occasionally, expresses a voice that could not have been previously raised.

And Dinah… went out… and he took her…" – traditional interpretation"

As is well known, Dinah's story appears in Parshat Vayishlach in the Book of Genesis, Chapter 34:

And Dinah, the daughter whom Leah had borne to Jacob, went out to see the daughters of the land. Shechem, son of Hamor the Hivite, chief of the country, saw her, and took her and lay with her and disgraced her. Being strongly drawn to Dinah, daughter of Jacob, and in love with the maiden, he spoke to the maiden tenderly. So Shechem said to his father Hamor, 'Get me this girl as a wife'. Jacob heard that he had defiled his daughter Dinah; but since his sons were in the field with his cattle, Jacob kept silent until they came home.

(Breishit 34:1-4)

These verses describe the starting point of a multi-participant story: Dinah, Shechem, Hamor – Shechem's father and the chief of the city of Shalem, the inhabitants of Shalem, Yaakov, and Yaakov's sons – Dinah's brothers, specifically Shimon and Levi. We are familiar with the plot – after Dinah is "taken" by Shechem who expresses his desire to marry her, his father and leader of the community – Hamor – approaches Yaakov and his family asking to arrange the marriage out of a willingness to negotiate the necessary terms. Yaakov's sons demand that Hamor and his community circumcise all the males in order to become "one people" (Breishit 34:17) and, after Hamor and Shechem successfully persuade them, a mass circumcision of all the males is conducted. While they are recuperating, Shimon and Levi come to the city and murder the entire male population, looting their property and livestock, abducting the women and children, and taking Dinah from the city. Yaakov confronts his sons with their actions, but the brothers insist that they did the right thing:

Jacob said to Shimon and Levi, 'You have brought trouble on me, making me odious among the inhabitants of the land, the Canaanites and the Perizzites; my fighters are few in number, so that if they unite against me and attack me, I and my house will be destroyed'".

But they answered, 'Should our sister be treated like a whore?'.

(Breishit 34:30-31)

The dramatic narrative, that evokes many thoughts and questions even when read superficially, is naturally the subject of much interpretation by biblical commentators. We can identify several common focal points of their interest and attention:

* The character of Dinah herself and her role in the events: is she at fault in any way and was her behavior responsible for this situation, or did she do nothing wrong?

* The meaning of Shechem "taking" Dinah and the motive behind this act: was it rape or not? Was the motive linked to status and honor stemming from Yaakov's standing and the fact that Dinah was an only daughter, to love, or maybe simply, to sexual desire?

* The act of depravity and the focus of sorrow and vengeance: is the act of depravity the act of rape, the sexual relations between an uncircumcised non-Jew and a daughter of Israel and specifically, Yaakov's daughter, or is this just an issue of failing to request permission from the head of the family in accordance with the accepted norms of the time? The assault is not necessarily against Dinah but, rather, against the family honor and accepted custom.

* Who is to blame and who is punished for what?

There are similarities scattered throughout the traditional interpretive sources: the focus on Yaakov and the family's standing and the question of the depravity and its impact, alongside an "investigation" of Dinah's behavior. Dinah herself, her will, and the ramifications on her life, receive only scant reference from the traditional commentators. Naturally, Dinah appears sporadically, but like her infrequent presence in the literal text, she is only a marginal "player" in the interpretive story. The examination of her character generally focuses on the opening verse of Chapter 34: "And Dinah, the daughter whom Leah had borne to Jacob, went out to see the daughters of the land" (Breishit 34:1). The commentators analyze the meaning of Dinah "going out" and "seeing the daughters of the land". Many of the commentators describe her actions as immodest (because of the linguistic connection between the Hebrew words for "going out" and "harlot") and even exegete that she intended to boast to the daughters of the land [1]. In other words, this is a view that attributes a certain, not insignificant, degree of blame for what happened to Dinah herself and her conduct. Another view specifically emphasizes Dinah's "innocence", whether on the basis of her ancestry as daughter of Yaakov and Leah as testimony to her proper behavior and modesty, or out of a practical analysis of the deeds of Shechem and identifying them as the primary causes for the subsequent events [2]. As mentioned, later commentary does not focus on Dinah bur rather, on the questions presented here: the motivation of Shechem, the meaning of the villainous deed etc.

When this discussion is examined from a contemporary viewpoint, it is impossible not to relate to the fact that this is, in many ways, an ancient version of the tendency to "blame the victim" and of erasing the woman from the set of considerations and decisions. This is clearly an anachronism and an entirely modern critique, but from a social and moral perspective, it is a necessary anachronism in order to recognize the problematic nature of such discussions and commentaries.

"And this is the Cry of the Heart" – A Modern Interpretation

The modern eye relies on numerous tools of literary-textual criticism alongside historical and academic analysis and enables a multiplicity of viewpoints beyond the classic tradition. This interpretive reality is possible largely thanks to the feminist movement and the presence of women in the interpretive domain and in public discourse, parallel to the renewed revelation or molding of history (from the female-feminine angle for example, there is the "her-story" trend). Modern and feminist commentary can extract voices from the biblical text that were not heard in traditional commentary, can highlight social and political structures, and can break down power relations and control [3]. It can examine the past, the present, and the future through eyes of social justice, morals and contemporary ethics.

In light of the dramatic content of Chapter 34 of Sefer Breishit, it is little wonder that countless articles, drashot and literary texts have been written in recent decades about the story of Dinah, Shechem, Shimon and Levi and Yaakov. Unlike the tendency of traditional commentary, modern commentary reflects a clear trend that aims to position Dinah at center stage and account for what she went through. One prominent example is, for example, Anita Diamant's book 'The Red Tent' – a novel that deals exclusively with the character of Dinah and her viewpoint [4]. Diamant chooses to present a tragic story of mutual love and desire between Dinah and Shechem which are interrupted by murderous violence and the massacre of Shechem and his city by Dinah's brothers. Diamant's book is viewed by many as an act of interpretive and feminist protest that grants an identity and voice to Dinah, her desires, her wishes, and which position her as a subject. Some, however, view this story as an anti-feminist move in light of the plot's "support" for Shechem and his actions and the framing of the narrative as a romantic and tragic love story while ignoring the violent aspects of Shechem's actions as described by the biblical text. In the monologue 'I am Sarah's aunt, and Rachel was my aunt' [5], Mira Magen presents Dinah's viewpoint, in identical fashion to Diamant. However, this monologue proposes an interpretation of Shechem's actions and Dinah's emotions that is diametrically opposed to that in 'The Red Tent':

…when Shechem came and did what he did, I didn't have a goat's fleece to bite, and my stifled cry escaped, and I was big and strong. 'Don't cry, girl', Shechem said, 'I love you; I will marry you, whatever dowry they ask for, girl, I will surely marry you.' I pray so hard for that cry of mine to return, so that I can utter it again.

The text clearly conveys that as far as Dinah is concerned, this is an unwelcome act – sexual relations that are forced upon her violently and without consent: rape.

Rivka Lubitch emphasizes the dimension of coercion and rape that Dinah experiences and her deafening silence. She exegetes and interprets Dinah story with a methodology similar to that of the classic interpretive midrash, but from a female-feminine viewpoint [6]:

'And Dinah… went out to see the daughters of the land' – Dinah was like a tail to her brothers. When she grew up and saw she had no place with them, she went out to see the daughters of the land, as is written: 'Either a friend for life or for death'. Dinah was mute-like, as it is written 'And Dinah went out to see…', to see and not to hear. And it is also written '…and lay with her and disgraced her' and it is not written '… and Dinah cried out'. Is it conceivable that Dinah did not cry out? But rather, she was mute, her pain and shame rendering her silent.

It was against her will. It is written 'he took her', teaching that Shechem abducted her. And it is further written '…and disgraced her', that speaks for itself.

Dinah's silence is from one end of the world to the other, and that is the cry of the heart.

Standing Alongside Dinah

Modern commentary and exegesis on the story of Dinah should not be taken for granted. This is not a subject that stood at the focus of communal or spiritual discourse decades ago. On the contrary, it was a subject that even aroused embarrassment when read in the synagogue and which was better to avoid, thereby preventing a discussion of disagreeable questions. The modern perspective enables us to examine the characters of the story – Shechem and Hamor, Yaakov and his sons – without fear, and to juxtapose the characters' actions with Dinah as an independent subject with a voice of her own. At this time, with all its pain and grief, we are asking to stand alongside Dinah. We must adopt an interpretive reading that acknowledges the voice of the injured and/or the silenced individual and must hold the community and society responsible for promoting standards of justice and compassion and aspiring to tikkun.

For further reading and discussion of the parsha and Dinah's story, you are welcome to access the informative content we have uploaded to 'Gluya' magazine, which incorporates numerous texts and sources.

[1] Rashi, Radak, Or HaChaim, Midrash Aggadah (Buber), Breishit Rabba, Midrash Lekach Shem Tov, Perush Hadar Z'keinim and many others on Breishit 34:1, focusing on "And Dinah… went out", on Dinah's genealogical relation to Leah (of whom it is also written that she "went out"), and Dinah's place on the axis of harlotry which is consistent with prostitution and lack of modesty.

[2] Rashbam, Malbim, R. Samson Raphael Hirsch, Pirkei D'Rabbi Eliezer, Bi'ur Yashar and others.

[3] Feminist commentary, Devora Evron (at a symposium held in memory of Ahuva Ben-Aharon).

[4] Anita Diamant, 'The Red Tent', St. Martin's Press, New York, 1977.

[5] 'I am Sarah's Aunt and Leah was My Aunt', from Ruth Ravitzky (ed.), Kor'ot Mibereshit: Women Read from the Beginning, Tel Aviv, 1999, pp. 275-9 (Heb).

[6] Rivka Lubitch, 'The Story of Dinah: The Bible, Chazal and Us', Avi Sagi and Nahem Ilan (eds.) Jewish Culture in the Eye of the Storm: A Jubilee Book in Honor of Yosef Ahituv, Hakibbutz Hameuhad 2002, pp. 742-753 (Heb).

רוצה לקבל עדכונים ממגזין גלויה?

הפרטים שלך ישארו כמוסים וישמשו רק למשלוח אגרת עדכון מהמגזין מפעם לפעם