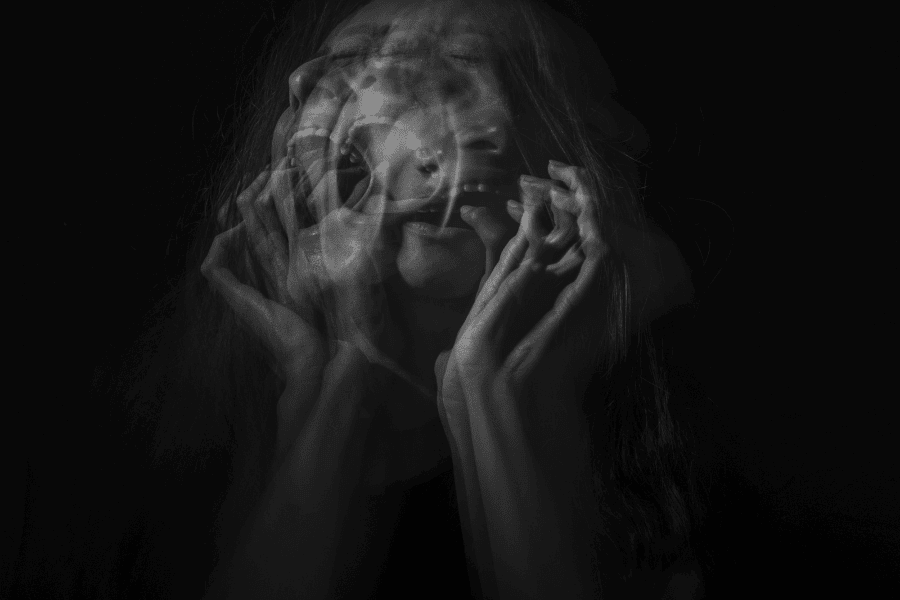

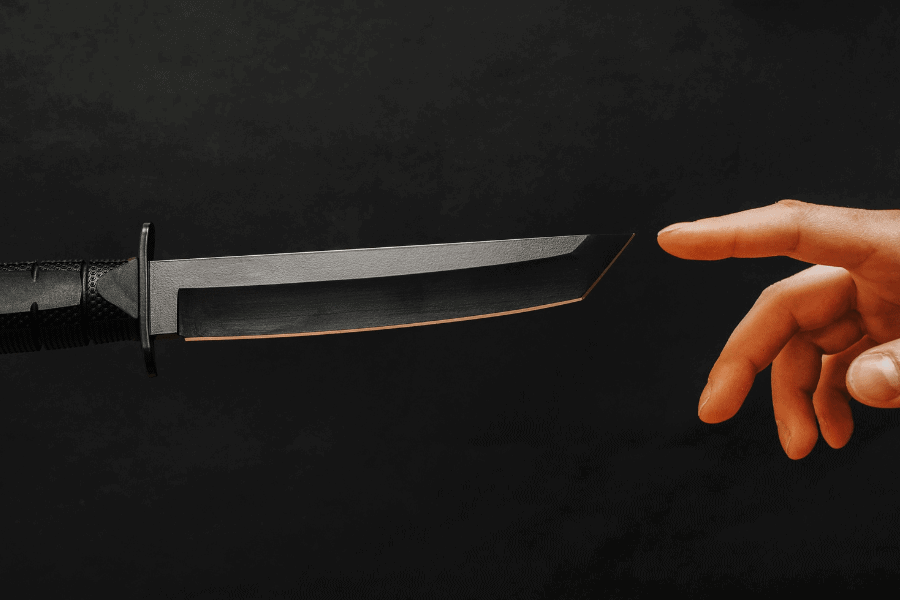

אזהרת טריגר

Trigger Warning

התוכן שלפניך עשוי להיות קשה לקריאה ומעורר רגשות של עצב וכאב.

אפשר לבחור לדלג ואפשר לבחור לעצור באמצע הקריאה.

מומלץ להקשיב לעצמך בזמן הזה.

הרב ד"ר גבי ברזלי מתבונן מחדש בדיני אונס ומפתה בחוקי המקרא בכדי למצוא את הציווי המוסרי – חינוכי שמתבקש מאתנו בימינו.

An English version appears immediately after the Hebrew text

מה הערך ללמוד את חוקי המקרא? איזה מסר רלוונטי אנחנו יכולים למצוא במערכת חוקים עתיקה כל כך, שמבוססת על הנחות יסוד חברתיות ומוסריות שונות כל כך מאלו שמקובלות בעולם שלנו? אחת הדוגמאות שמייצגות את הדילמה הזאת במלוא חריפותה הוא החוק העוסק בדינו של אונס בתולה (דברים כב 29-28) – חוק מקומם והזוי בעיני כל קורא בן זמנינו.

מישהו תופס נערה צעירה ברחוב חשוך או בשדה, כופה את עצמו עליה ואונס אותה. מעשה נבלה שאין כדוגמתו, מעשה שהתורה עצמה, רק פסוקים מעטים לפני כן, משווה לרצח (דברים כב 26), ומה דינו? "וְנָתַן הָאִישׁ הַשֹּׁכֵב עִמָּהּ לַאֲבִי הַנַּעֲרָה חֲמִשִּׁים כָּסֶף, וְלוֹ־תִהְיֶה לְאִשָּׁה תַּחַת אֲשֶׁר עִנָּהּ לֹא־יוּכַל שַׁלְּחָהּ כָּל־יָמָיו" (דברים כב 29). זה הפתרון? לחייב אותו להתחתן איתה? לחייב אותה להתחתן איתו? האם מישהו שאל אותה בכלל אם זה מתאים לה? פתרונות שכאלה נראים לנו היום לא מוסריים, בלתי מתחשבים, מוסיפים חטא על פשע, הזויים.

בפוסט קצר שכתב צחי לב-רן למיזם 929, הוא מעלה את כל השאלות האלו וגורס שכדי להבין את חוק התורה לאשורו יש צורך להשוות אותו לחוקי אונס בקבצי חוקים אחרים מתקופת המקרא. למזלנו, מצויים בידינו כתבים משפטיים וקבצי חוקים לא מעטים מהמרחב הגאוגרפי-היסטורי של המזרח קדום, חלקם בני זמנו של המקרא, אחרים קודמים לו בעשרות ובמאות שנים. מתוך המאגר הטקסטואלי הזה ניתן ללמוד רבות על הייחס לנשים בתקופת המקרא, על משמעות הנישואין, ועל המשמעות שיוחסה לאונס ולאנסים בעולם המשפטי שבו התפתחו גם חוקי המקרא.

מתוך ההשוואה הזאת, מגיע לב-רן למסקנה שהיחס לנשים שמשתקף בחוק אונס בתולה בתורה, ממש כמו בחוק המקביל לו בספר שמות – דינו של מי שמפתה בתולה (שמות כב 16-15), מוסרי ומתחשב בהרבה מחוקים מקבילים בעולם שמסביב. כיוון שהנישואין בעולם העתיק (למעשה, עד המאה האחרונה ממש) היו הסכם כלכלי-חברתי בין משפחות שנוהלו על ידי אבות המשפחה, וכיוון שבתוליה של הנערה נחשבו לנכס כלכלי של אביה, הרי שהחוק המקראי דואג למעמדה הכלכלי-חברתי-משפטי של הנערה. חיוב האנס להתחתן עם הנאנסת מטיל עליו את האחריות לשלומה ולרווחתה לכל ימי חייו, וזה מה שחשוב לתורה להדגיש. אדם אחראי למעשיו ומקבל על עצמו את האחריות לכל התוצאות הנלוות של מעשיו, בין אם התכוון להן ובין אם לא. ומה באשר לרגשותיה של הנאנסת? אלו אינם מהווים שיקול בפסיקה.

רוצה לקבל עדכונים ממגזין גלויה?

הפרטים שלך ישארו כמוסים וישמשו רק למשלוח אגרת עדכון מהמגזין מפעם לפעם

ועדיין לא נחה דעתנו. גם אם למדנו שתורה רואה לנגד עיניה את מעמדה הראוי של האישה, בימי קדם, גם אם הבנו שתורה מטילה על האדם אחריות מלאה למעשיו, עדיין איננו מסוגלים לקבל את הפתרון המשפטי שמציעה התורה לנערה הנאנסת. אז ערך חינוכי או חברתי יש למידע הזה?

מתוך הניתוח של צחי לב-רן אפשר להציע את הדרישה המשפטית-מוסרית הבאה. כפי שחוקי נשים במקרא משקפים יחס מכבד יותר לנשים, בהשוואה לעולם שמסביב, כך גם מערכות החוק והמשפט היהודי-ישראלי בימינו חייבות להתייצב בחזית השאיפה לשוויון בין המינים ולהיאבק על כבודן של נשים, על זכויותיהן ועל שלומן, יותר ממערכות משפטיות וחוקיות של מדינות ותרבויות אחרות בנות זמנינו. הלוואי שנעמוד בדרישה זו.

אני מבקש להציע פתרון נקודתי יותר לעונשו של אנס, שמשתמש במסקנות המשפטיות של החוק המקראי ומתרגם אותן למושגי חובות וזכויות מודרניים. מובן שאין כל הצדקה מוסרית או משפטית לחייב את הנאנסת להתחתן עם האנס, אבל חובתו לדאוג לרווחתה, לשלומה, לבריאותה הנפשית והגופנית, למשך כל ימי חייו בעינה עומדת. במערכת המשפטית הנהוגה כיום בישראל, כמו ברוב מערכות החוק והמשפט בעולם המערבי, מחויבות זו איננה נלקחת בחשבון. אנסים נשפטים כפושעים פליליים שפוגעים בחברה, ונענשים בעונשי מאסר. שלומה ומצבה של הנאנסת הוא משני במהלך המשפט ובמקרים רבים כלל לא מהווה שיקול בסוג העונש או בחומרתו. במקרה הטוב יטילו בתי המשפט פיצוי כספי חד פעמי על האנס, לטובת הנאנסת, ובמקרים רבים גם זה לא. אבל אם נאמץ את העקרונות של המשפט המקראי, יידרשו השופטים לחייב את האנס לשלם לנאנסת תשלום חודשי קבוע, לכל ימי חייו, תשלום שמותאם לצרכים הכלכליים של הנאנסת. תשלומים קבועים שכאלה יסייעו לנפגעות לעמוד על רגליהן, ומצד שני יחייבו את הפוגעים באחריות מלאה לתוצאות מעשיהם.

Rabbi Dr. Gabi Barzilai takes a new look at the laws pertaining to rape and seduction in the bible in an effort to identify the moral-educational imperative required of us today.

What is the value in studying the laws of the bible? What relevant message can we derive from such an ancient system of laws, one based on social and moral conventions so different from those accepted today in our own world? One example representing the full acuteness of this dilemma is the law in the case of the rape of a virgin (Deut. 28-29) – an outrageous and outlandish law in the eyes of any contemporary reader.

Someone catches a young woman in a dark street or in a field, forces himself on her and rapes her. A deplorable act of unparalleled despicability, one that the Torah itself, only a few verses previous, compares to murder (Deut. 22:26). And the rapist's punishment? "The party who lays with her shall pay the girl's father fifty [shekels of] silver, and she shall be his wife. Because he has violated her, he can never send her away as long as he lives" (Deut. 22:29). That's the solution? Obligating him to marry her? Compelling her to marry him? Did anyone even ask her what she wants? By today's standards, such solutions seem immoral, inconsiderate, adding insult to injury, even bizarre.

Tzachi Lev-Ran, in a short post he wrote for the '929' Project, raises all these questions and suggests that in order to properly understand the law of the Torah, it must be compared to laws pertaining to rape in other legal codes from the biblical era. Fortunately, we have a number of legal texts and codes from the Near East geo-historical world, some of which are from the biblical period, while others predate it by decades or even centuries. This textual repository is a source of considerable information about the attitude to women in the biblical era, the meaning of marriage, and the significance attributed to rape and rapists in the legal world in which the laws of the bible also evolved.

This comparison leads Lev-Ran to conclude that the attitude to women reflected in the Torah law pertaining to the rape of a virgin, just like the parallel law in the Book of Exodus that relates to a person who seduces a virgin (Exod. 22:15-16), is significantly more moral and considerate than many of the relevant laws in the surrounding culture. Because marriage in the ancient world (in practice, until the last century) was a socio-economic agreement between families run by their fathers, and because a young woman's virginity was regarded as an economic asset belonging to her father, the biblical law is primarily concerned with preserving the woman's socioeconomic-legal status. Obligating a rapist to marry his victim imposes on him the responsibility for her well-being and welfare for the rest of his life, this being the salient point emphasized by the Torah. A person is accountable for his actions and assumes the responsibility for all resultant ramifications, whether intended or merely consequential. As to the victim's feelings, these play no role in the judicial process.

However, this is still insufficient. Even if we accept that the Torah had proper consideration for the rightful standing of women in ancient times, even if we acknowledge that the Torah holds a person to be fully responsible for his actions, we cannot nevertheless accept the legal solution proposed by the Torah for the rape victim. What then is the educational or social value here?

Tzachi Lev-Ran's analysis may form the foundation for the following legal-moral demand. Just as biblical laws pertaining to women reflected a more respectful attitude towards them compared to those in the surrounding culture, so too today's Jewish-Israeli legal and judicial systems should likewise lead the aspiration for gender equality and the struggle for women's honor, rights and wellbeing, more than legal and judicial systems of other modern-day countries and cultures. May we merit to meet that demand.

I wish to propose a more specific solution for the rapist's punishment, one that uses the legal conclusions of the biblical law and translates them into modern concepts of rights and obligations. There is naturally no moral or legal justification for compelling the rape victim to marry her rapist, however his obligation to care for her welfare, safety, mental, emotional and physical wellbeing for the rest of his life remains unchanged. Under Israel's current legal system, like that of most legal and judicial systems in the western world, this obligation is simply not taken into consideration. Rapists are judged as criminals who harm society and are punished with prison terms. The victim's welfare and her physical and emotional state are a secondary factor during the trial and, in many cases, play no role when deciding the type or severity of punishment. At most, the court will impose a one-time reparations payment on the rapist to be paid to the victim but even this is frequently dispensed with. If, however, we adopt the principles of biblical law, the judges will be required to impose upon the rapist a fixed monthly payment to the victim for the rest of his life, a payment designed to meet her financial needs. Such regular payments will help victims' rehabilitation, while at the same time ensuring that perpetrators assume full responsibility for the consequences of their actions.

תכנים נוספים על ״שבוע דינה״:

רוצה לקבל עדכונים ממגזין גלויה?

הפרטים שלך ישארו כמוסים וישמשו רק למשלוח אגרת עדכון מהמגזין מפעם לפעם

המלצות לקריאה נוספת במגזין גלויה:

- ותצא דינה: להישיר מבט ולהיות איתה שם בכאבה – צביקי פליישמן

- שכם ודינה – סיפור אהבה או התעללות? – פסית שיח

- מדרש יוסף ודינה – הרבנית שלומית פיאמנטה

- קריאה חדשה בסיפורי דינה – ד"ר גילי (מבצרי) זיוון

- מדרשי דינה – טו״ר רבקה לוביץ

- מי את אסנת בת פוטי-פרע? אשת יוסף בפרשנות מימי הבית השני ובפרשנות חז"ל – הרב ד״ר גבי ברזלי

- מה יש לדבר על דינה? בית מדרש חדש על סיפור ישן – יורם גלילי

- ותצא דינה – מחשבות בשעת מלחמה / And Dinah went out – הרבנית מיכל כהנא

- מקורות ללימוד ועיון בסיפור דינה – פרשת 'וישלח' – צוות גלויה

- להטות שכם אל דינה: רשומה לקראת פרשת 'וישלח' וסיפור פגיעתה של דינה – צוות גלויה

- סיפור דינה – איך לדבר את הטראומה? – אורי שרמן-קנוהל

קווי החירום לנפגעות ולנפגעי תקיפה מינית

שאלון זיהוי למצבי סיכון

שאלון אנונימי של משרד הרווחה שנכתב עם מומחים לטיפול

כדי לזהות את מצבך או את מצב הסיכון של בן או בת משפחה ובסביבתך הקרובה.